Although 8-year-old Randy Reeves faces the possibility of complete deafness, he is every bit a typical kid. The story was done by the author during the Missouri Photojournalism Workshop held in Caruthersville, Mo. in 1987, as part of his fellowship at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Facing a Silent Future

“Mom, are you proud of me?” Randy Reeves of Caruthersville, Mo., asks. “Yes, I am,” she answers. Breaking into a wide smile, he walks over to her and gives her his biggest hug.

Her reply means a lot to Randy, who at the tender age of 8 has already lost 70 percent of his hearing.

Such an impairment does not keep this spunky boy from enjoying the world around him. Now armed with a pair of special hearing aids, he’s ready to conquer everything. Like any 8-year-old, he goes to school and spends his free time playing with his toy truck, climbing trees and, at times, just being silly.

Randy has a congenital hearing problem that his mother, Cindy Davis, 24, learned about when he started school. She remembers that at the time her son spoke like a baby; all he could say coherently was “mom” and “daddy.” No one in his kindergarten class could understand him, not even his teacher. As a result, Randy had to go through kindergarten twice and attend a special speech class. Nevertheless, he scored only 5 percent — the lowest in the school — on the Science Research Associates test.

His teacher advised his mother to see a doctor concerning what they supposed was a hearing problem. “I cried for I don’t know how long,” Davis recalls.

Fortunately, the cost of Randy’s medical treatment is being handled by the Missouri Crippled Children’s Fund. His hearing aids cost $1,200 apiece, and consultation fees will run from $70 to $100. His stepfather, Zack Davis, 23, is a construction worker; his mother is a cook at the Tennessee Inn in Caruthersville. Randy has a younger brother, Brandon, who is 4. Randy’s father, Tim Harris, is in the military, stationed in Germany, and hasn’t seen the boy since he was 2. Randy uses his mother’s maiden name.

With a hearing loss of 70 percent, Randy begins to respond to sounds at a frequency of 90 decibels. For a person with normal hearing, 90 decibels would cause a significant amount of pain. His actual hearing range is from 60 to 90 decibels.

When Randy entered first grade, the school’s administration placed him in a special class. After one year, he took another S.R.A. test and scored 52 percent, a quantum leap from his previous score.

But as grades improved his hearing deteriorated. “His hearing just dropped last January after holding its own for a while,” says Randy’s speech pathologist, Patty Abbott. Concerned that the boy’s condition would only worsen, the school started a sign language class for him as he entered the second grade.

Randy showed a strong aptitude for sign language. He learned 23 signs in 30 minutes on the first day. He now learns an average of 30 to 40 signs a week. “He is capable of doing anything he likes to do,” Abbot says, “but math is hard for him.”

In class, his teacher, Diana Cox, uses a voice-sound transmitter called the Frequency Modulator system. This special device amplifies her voice in the receiver connected to Randy’s hearing aid. Without the FM system, the hearing aid would amplify all sounds, creating an experience similar to that of a noisy marketplace.

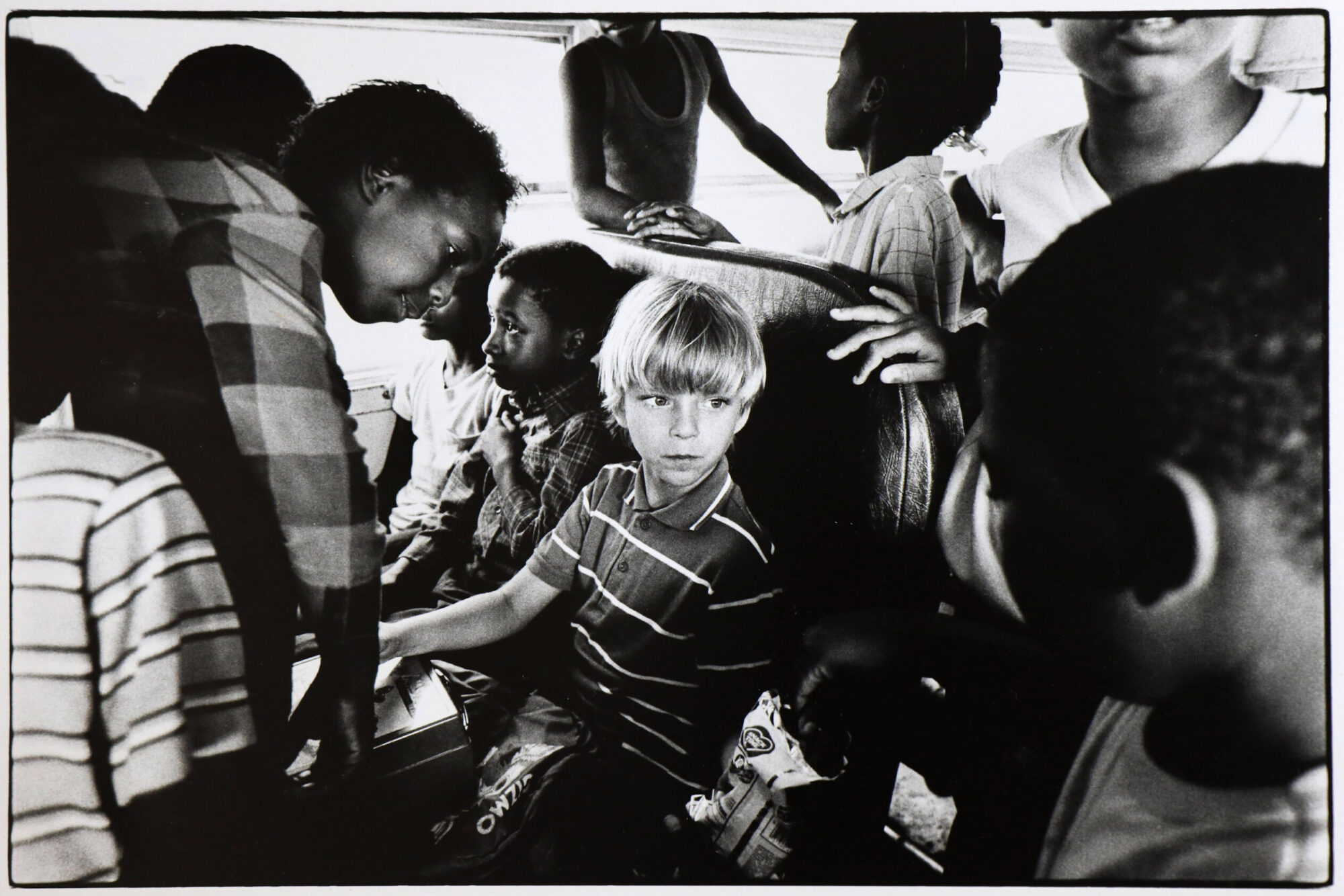

Randy attends class regularly. He also solves math problems on the blackboard, submits his spelling work on time and plays computer games with his classmates. He has excellent rapport with his classmates and usually shares his signs and sign language book with them while waiting for the bus. He also likes sneaking into neighbors’ houses and trading toys with other kids.

Like typical 8-year-old boys, Randy has a mischievous streak. “Randy, at times, takes advantage of his disability,” Tom Porter, principal of South Side School, says. “He pretends not to hear you. Sometimes he even turns off his hearing aid.”

At home, Randy teaches sign language to his mother and brother. Though the future of Randy’s hearing is uncertain, he takes it with a kind of child-like casualness. Once, when asked how he would feel if he should lose his hearing, “sad” was all he said.

“Mom, are you proud of me?” he asked her one day. “Yes, I am,” she replied.

No sound could have been sweeter.

Photographs and story by Claro Cortes IV. Ⓒ All Rights Reserved.